from sonorensis, Volume 16, Number 1 (Spring 1996)

Thomas E. Sheridan, Curator of Ethnohistory

Arizona State Museum

University of Arizona

When Anglo American soldiers and gold-seekers first crossed the Sonoran Desert in the late 1840s, they did so begrudgingly. "What this God-forsaken country was made for," one forty-niner wailed, "I am at a loss to discover." Dr. John S. Griffin, who accompanied General Kearny's Army of the West during the Mexican War, wrote, "Every bush is full of thorns...and every rock you turn over has a tarantula or centipede under it. The fact is, take the country altogether, and I defy any man who has not seen it-or one as utterly worthless-even to imagine anything so barren." To these early sojourners, Arizona was nothing but a dangerous obstacle-hot, parched, and desolate. California was always the prize.

More than a century later, however, a report by the Hudson Institute entitled Arizona Tomorrow claimed that Arizona had managed to redefine "the very term desert." Desert,

Arizona style, now meant "an appealing landscape, an attractive place to live, and a new kind of adult playground." According to Arizona Tomorrow, "Desert living with air conditioning, water fountains, swimming pools-getting back to nature with a motorized

houseboat on Lake Powell (itself a man-made lake), and going for an ocean swim in a man-

made ocean are all contemporary examples of the marriage between life-style and technology."

More than a century later, however, a report by the Hudson Institute entitled Arizona Tomorrow claimed that Arizona had managed to redefine "the very term desert." Desert,

Arizona style, now meant "an appealing landscape, an attractive place to live, and a new kind of adult playground." According to Arizona Tomorrow, "Desert living with air conditioning, water fountains, swimming pools-getting back to nature with a motorized

houseboat on Lake Powell (itself a man-made lake), and going for an ocean swim in a man-

made ocean are all contemporary examples of the marriage between life-style and technology."

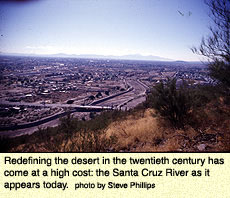

What caused our perceptions of the desert to change so radically? The answer is simple: water. Redefining the desert meant pouring massive amounts of water onto it. Gravity caused runoff from the Rockies to surge down the Colorado River and rainfall from thousands of years of desert storms to percolate down through the alluvium to create underground aquifers. Whether with pumps, canals, or dams, modern Arizona history has been one long reversal of gravity. In the modern West, water flows uphill toward money. Cheap energy makes this astonishing feat of legerdemain possible.

What caused our perceptions of the desert to change so radically? The answer is simple: water. Redefining the desert meant pouring massive amounts of water onto it. Gravity caused runoff from the Rockies to surge down the Colorado River and rainfall from thousands of years of desert storms to percolate down through the alluvium to create underground aquifers. Whether with pumps, canals, or dams, modern Arizona history has been one long reversal of gravity. In the modern West, water flows uphill toward money. Cheap energy makes this astonishing feat of legerdemain possible.

The transformation did not happen overnight. During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, thousands of Anglo Americans settled in the Arizona desert but few of them viewed it as an "adult playground." On the contrary, they came to Arizona to rip its natural resources out of the ground and ship them someplace else for finishing and processing. This was the era of extraction, when Arizona was dominated by the so-called Three C's of cattle, copper, and cotton. Most of the capital to stock Arizona's ranges and dig its copper came from outside the territory (Arizona became a state in 1912). In a political as well as economic sense, Arizona was an extractive colony of business interests in the eastern United States and Western Europe.

Those interests never would have invested in southern Arizona were it not for the Southern Pacific Railroad. In 1880, the Southern Pacific drove its largely Chinese crews across the Sonoran Desert in order to link California with the rest of the United States. The Southern Pacific had little interest in Arizona, yet the completion of the transcontinental line revolutionized Arizona's economy. Without the railroad, the mining of low-grade copper ore never could have made a profit, and copper-mining communities like Superior, Hayden, San Manuel, and Ajo never would have developed. The railroad also allowed Arizona ranchers to sell their cattle and sheep in California and the Midwest. During the 1880s, ranchers drove cattle and sheep into every corner of Arizona, including the Sonoran Desert, and miners burrowed hundreds of miles beneath Arizona's hard ground.

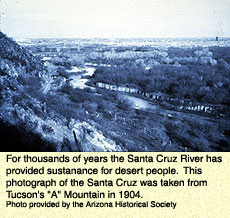

The impact upon Arizona's environment was devastating. Before the widespread adoption of electrically powered machinery,woodcutters denuded river valleys and hillsides by cutting thousands of cords of mesquite and oak to fuel ore-crushing stamp mills. Meanwhile, 1,500,000 cattle and more than a million sheep grazed Arizona ranges down to the soil. Arroyos incised most of southern Arizona's rivers and streams. Professional hunters decimated deer, pronghorn, and bighorn sheep populations and exterminated grizzlies and wolves to feed the miners and reduce livestock predation. Photographs at the turn of the century show a lunar landscape in places as extraction took its toll.

But the twentieth century brought new constituencies to Arizona-constituencies that would eventually challenge the extractive interests and demand the protection of Arizona's natural beauty and cultural heritage. President Teddy Roosevelt, an avid hunter and conservationist, incorporated the mountain islands of southern Arizona into the forest reserve (later the national forest) system. Tourists flocked to dude ranches on the outskirts of Tucson, Phoenix, and Wickenburg. Artistic visionaries like John C. Van Dyke even argued, "The deserts should never be reclaimed. They are the breathing spaces of the west and should be preserved forever." Arizona's public lands became a battleground where contesting visions of the environment struggled for Arizona's soul.

Sooner or later, the arguments always returned to water. In the early 1900s, the newly created federal Reclamation Service joined forces with the farmers of the Salt River Valley to build Roosevelt Dam. For nearly 2,000 years, floods surging down the Salt had devastated Hohokam, O'odham, Mexican, and Anglo American farmers. Roosevelt Dam tamed the Salt and enabled the Salt River Project (SRP) to turn the valley into the largest oasis of commercial agriculture in the southwestern United States. During World War I, after Britain embargoed the world's supply of long-staple cotton (necessary for tire fabric and other industrial uses) in Egypt and the Sudan, tire companies like Goodyear and Firestone turned to the Salt River Valley with its hot, dry growing season to fill their War Department contracts. Between 1916 and 1920, long-staple cotton cultivation rose from 7,300 acres to 180,000 acres in the Salt River Valley alone, and the cotton boom began.

In Arizona, every boom has its bust, and the visions of one generation are quickly replaced by the visions of another. Both the Salt River Project and the Central Arizona Project were conceived as farmers' dreams to make the desert bloom. Beginning with World War II, however, Salt River Project water and hydroelectric power fueled the explosive growth of metropolitan Phoenix, which developed into an urban center of nearly 2,500,000 people. Subsidized by the federal government, the Central Arizona Project now flows 335 miles uphill toward money, but few farmers can afford its water. Arizona is completing its transformation from an overwhelming rural state dominated by extractive industries to an overwhelmingly urban society where few people make their living as ranchers, farmers, or miners anymore.

Will that urban society treat the desert any kinder? Or will we simply set aside a few more refuges while subdividing the rest? In the nineteenth century, most Anglo Americans passed through Arizona on their way to California, and Arizona suffered from a bad case of California envy. Now the flow of people and capital is reversing itself as smog, high taxes, and skyrocketing real estate values make California less appealing. Arizona's future may well be like that old warning from our mothers: Be careful what you wish for because it may just come true.

Tom Sheridan is author of Arizona: A History (University of Arizona Press, 1995).